It was that moment, when I watched “Interstellar” for the 20th times,

That I realized I didn’t just like to write or to read.

More than that, I’m fascinated with stories.

Tell me stories, and we are best friends.

So, this is the movie I had been waiting for more than a year, and in my case, I think that’s the first time I was impatiently waiting for months for something to come. I told you that I was waiting for three big reveals in 2017, and beside Dan Brown’s Origin and Tesla Model 3, the other one was this Dunkirk (2017) movie, the latest work of Christopher Nolan. You can call me a Chris Nolan fan boy, that’s fine, because what I did at July 21st, 2017 when the movie first came out was what a fan boy would actually do. I literally ran after hitching an ojek to the nearest theater as soon as my work done in the evening, and didn’t catch a breath until I hold one ticket in my hand. *Yep, I watched it alone even after I promised bang Satria a month earlier to watch it with him, just because I couldn’t help to wait any longer. Not to mention how many times I watched the trailer, studying every released material about the movie, looking up the actors’ profile, and counting the days until the premiere.

I had never been that prepared just to see a film, and so my expectation was high. And that’s reasonable because Nolan’s works always live up to it, and he himself who set the bar of expectation so high by making great movies, one after the other.

Then I came to watch the movie. And this is more of my experience than a review.

*

Throughout its 106 minutes length, these are basically my stage of feelings when I watched the movie.

- First 30 minutes : “Whoa! Yes, finally!”

- 31 – 60 minutes: “Who is he? Who are they? Why are they doing that?”

- Last 40 minutes: “…”

I was speechless.

I left the theater with mixed feelings. Not because it was bad, but because, it was just something different from my expectations. I wasn’t going to call it disappointing, but more of something that I never pictured before. You know, I was a basic movie-goer, and with my list of all Nolan’s feature films that I’d watched, I was expecting something like The Dark Knight (2008), Inception (2010), or Interstellar (2014). It was like expecting more powerful horse to ride, but someone gave you a car instead. At first you don’t understand, or even disappointed, but you know it brings something better in the end.

By the time my feet reached the exit door, I promised to myself that I had to re-watch that movie as soon as its home video version was released, and had to write something about it. *And here I am, got the movie earlier last month, but a month late to write it down.

The Script and The Choice of Lesser Dialogues

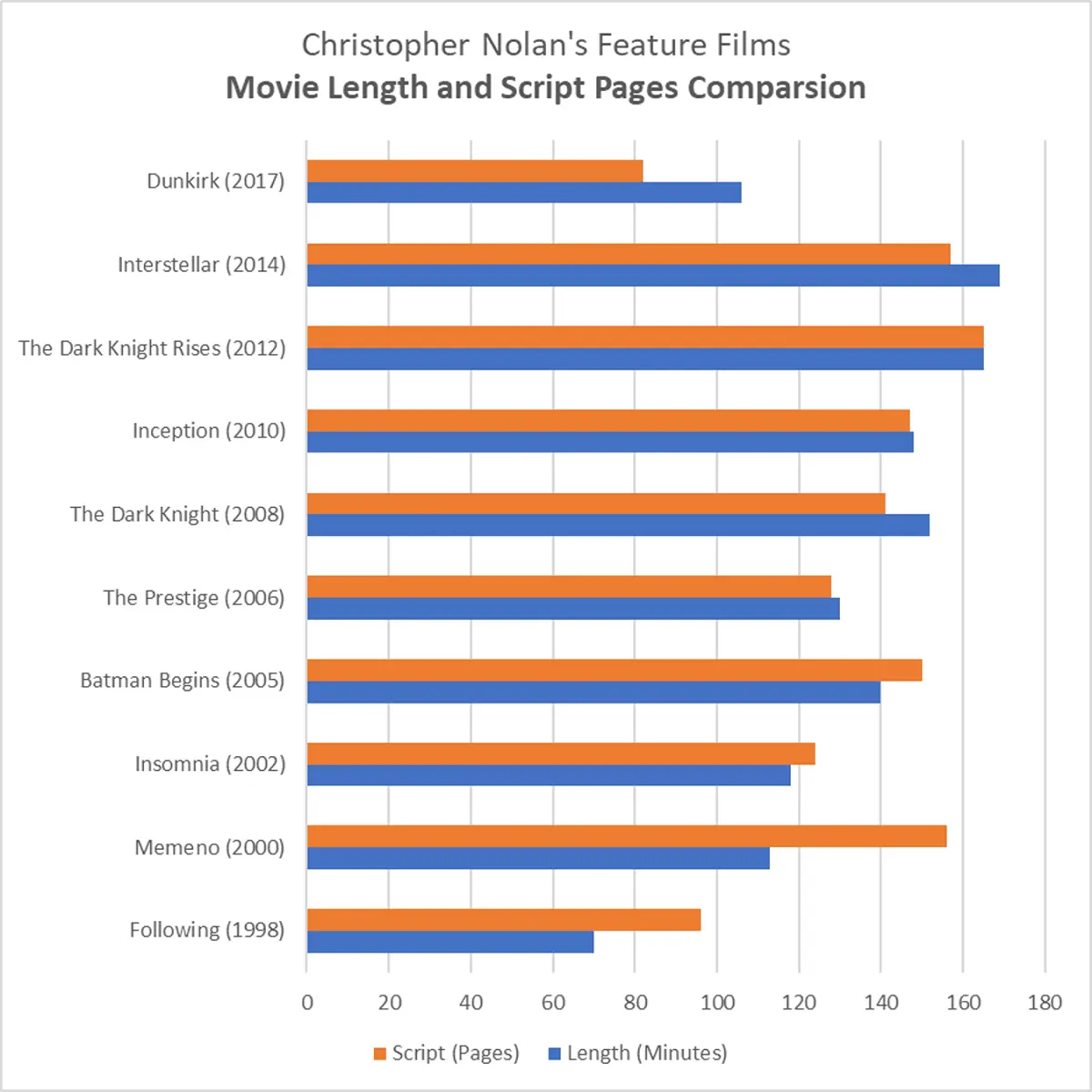

I’ve been collecting all of Christopher Nolan’s movie scripts, all 10 of his released feature films, from the indie debut Following (1998) to Dunkirk (2017). And at a first glance, it’s easy to notice that the Dunkirk script was by far the shortest Nolan’s work. It’s even 14 pages shorter than the Following’s, even though Dunkirk has 36 minutes longer in length.

There’s an unwritten law in script writing technique stating that one page of the script equals to one minute of the film. Yes, it doesn’t apply to every case, but that basic rule makes movie scenes detailed enough to follow and enjoy, not too long to make us bored, nor too short to make audience confused. *You can learn more about this here. So, in Dunkirk’s case it makes me questioned that 82 pages script turned into 106 minutes film, there must be a catch.

And the answer was the director’s choice to make that movie lesser in dialogues, indeed. He chose to create a film to have little dialogues, and instead of trying to engage audience with spoken narratives, it tried to engage audiences with visual spectacles. That, is what made some audience confused throughout the movie. They used to look at screen and follow the actors talk, telling what they came from, how did they end up there, how’s their family, etc. But in Dunkirk, we were brought the actions seconds after the movie started, and that’s relatively what happened until the movie ended. We weren’t given a chance to learn the characters’ family and their motives, and how they ended up in situations like that. All we watched in Dunkirk was what happened in the history of Evacuation of Dunkirk.

It’s never about the characters’ personal stories.

It’s all about the events.

In the end, it sacrificed some portion of fans that wasn’t patient enough to see the whole movie without knowing who they’re watching. I found some people walked out of my theater in the middle of the movie. That made sense, even I admit that I was also confused in some parts of the movies, and I couldn’t bare to see the story going on without knowing what or who I was watching. It’s like we weren’t engaged enough to the characters because we didn’t know them, because they never told us, because we couldn’t empathize to their struggles.

But what held me to sit down still to the last second of the movie was my trust in Nolan, that he still had that power to bring us a better and the best movie he could create. *At least that’s what a fan would do.

At last, the box office and critics paid off. It was successful in grossing while also getting praised by reviews. Some considered that it was one of the best war movie ever made, pointing out that lesser dialogues and focusing more on the event was a precisely how a war should be reenacted, not too much chit chat and pretending there were no horrors going on.

I can go on talking more about this movie: about Hans Zimmer’s music, which is great as always; about the choice of Actors which a little bit off of Nolan’s habit, leaving Hollywood-centric tradition, and Harry Styles joining the cast that made girls went crazy; also about the props used from real World War II vehicles. But you can dig it yourself, and I’m more interested about the script and the artistic choices.

The Triptych

In one of Nolan’s interview before Dunkirk was released, he teased about the film’s unique structure, which he called like a triptych, “a work of art (usually a panel painting) that is divided into three sections, or three carved panels that are hinged together and can be folded shut or displayed open” (Wikipedia). He quoted:

“The film is told from three points of view. The air (planes), the land (on the beach) and the sea (the evacuation by the navy). For the soldiers embarked in the conflict, the events took place on different temporalities. On land, some stayed one week stuck on the beach. On the water, the events lasted a maximum day; And if you were flying to Dunkirk, the British spitfires would carry an hour of fuel. To mingle these different versions of history, one had to mix the temporal strata. Hence the complicated structure; Even if the story, once again, is very simple.”

I’m not going to be an all-knowing explainer here, but this specific narrative style he chose here fascinated me. The story was pretty much basic events on what’s happening in different locations in Dunkirk, and the common technique to tell that stories would be generic cut scenes from one place to another, from one character-arc to another. Instead, Nolan saw that chance to depict the intermingled events of Evacuation of Dunkirk and showed the audience how the war happened in a real context: people working on different places, from different backgrounds, with different context, aiming towards one similar hope for victory.

They who patiently watched the movie to the end would understand that the story was a block set of inter-related narratives. It can be seen as a whole, one unit of an artistic movie, or as three separated arts:

The History: “We Shall Never Surrender”

“This is an essential moment in the history of the Second World War. If this evacuation had not been a success, Great Britain would have been obliged to capitulate. And the whole world would have been lost, or would have known a different fate: the Germans would undoubtedly have conquered Europe, the US would not have returned to war. It is a true point of rupture in war and in history of the world. A decisive moment. And the success of the evacuation allowed Churchill to impose the idea of a moral victory, which allowed him to galvanize his troops like civilians and to impose a spirit of resistance while the logic of this sequence should have been that of surrender. Militarily it is a defeat; On the human plane, it is a colossal victory,” -Christopher Nolan.

When I studied part of history of WW2 surrounding the Evacuation of Dunkirk, I ended up more interested in Winston Churchill’s speech, called “We Shall Fight on the Beaches”. At that time Churchill was the British Prime Minister, elected just eight months after the outbreak of World War II. The speech was noted as one of three major speeches addressed around the period of the Battle of France, along with “Blood, Toil, Tears, and Sweat”, and “This Was Their Finest Hour”.

What’s remarkable about the speech, along with two others, is that it was powerful enough to lift the morale of the nations, both UK and in France, to defend their country against the Nazis**. It was a very difficult time when the victory seemed far, the Nazis had cornered the allies, and there was no help to seek out.** But the speech alone, if not others, had successfully carried the dramatical change over the five-week period of the Battle of France, assuring both civilians and soldiers to think and act that led them to the success of Evacuation of Dunkirk -which was also the turning point of Nazis defeat, and finally led the allies to win the World War II.

And Nolan had carefully quoted the speech into his work in Dunkirk, beautifully crafted so that we can enjoy the movie while also reliving the spirit of fight for victory in it:

“We shall go on to the end.

We shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills;

We shall never surrender.”